The Changing Hands blog series explores the backstories of books in Special Collections by focusing on the readers who owned them before they were acquired by the Binghamton University Libraries.

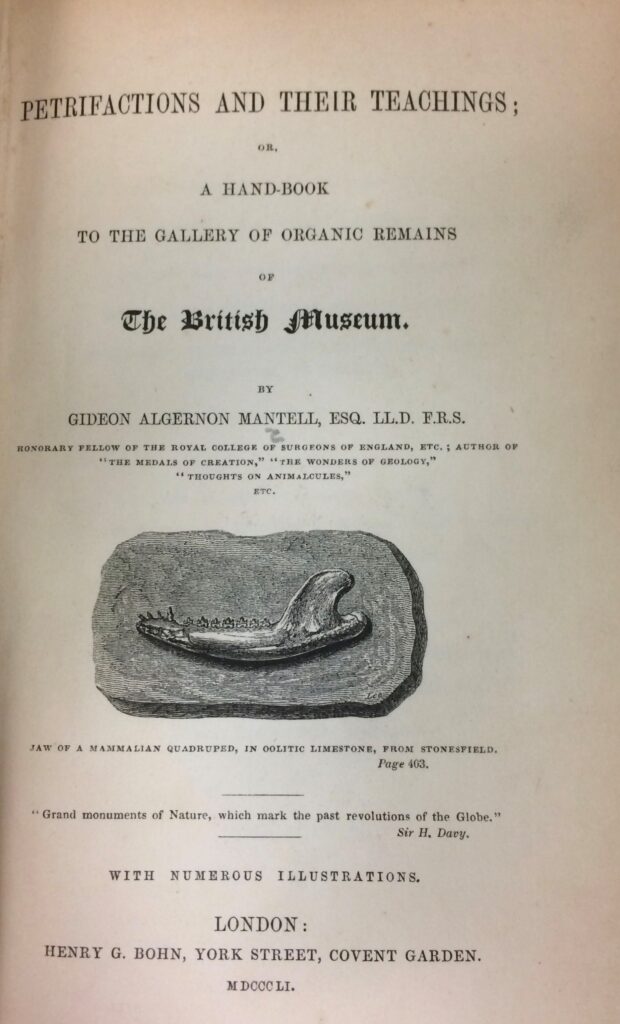

We resume this blog series with a book which was transferred to Special Collections from the Science Library in late 2019: Gideon Algernon Mantell’s Petrifactions and their Teachings: or, a Hand-book to the Organic Remains of the British Museum (London: H.G. Bohn, 1851). You can read a full scan of another copy of the book via the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

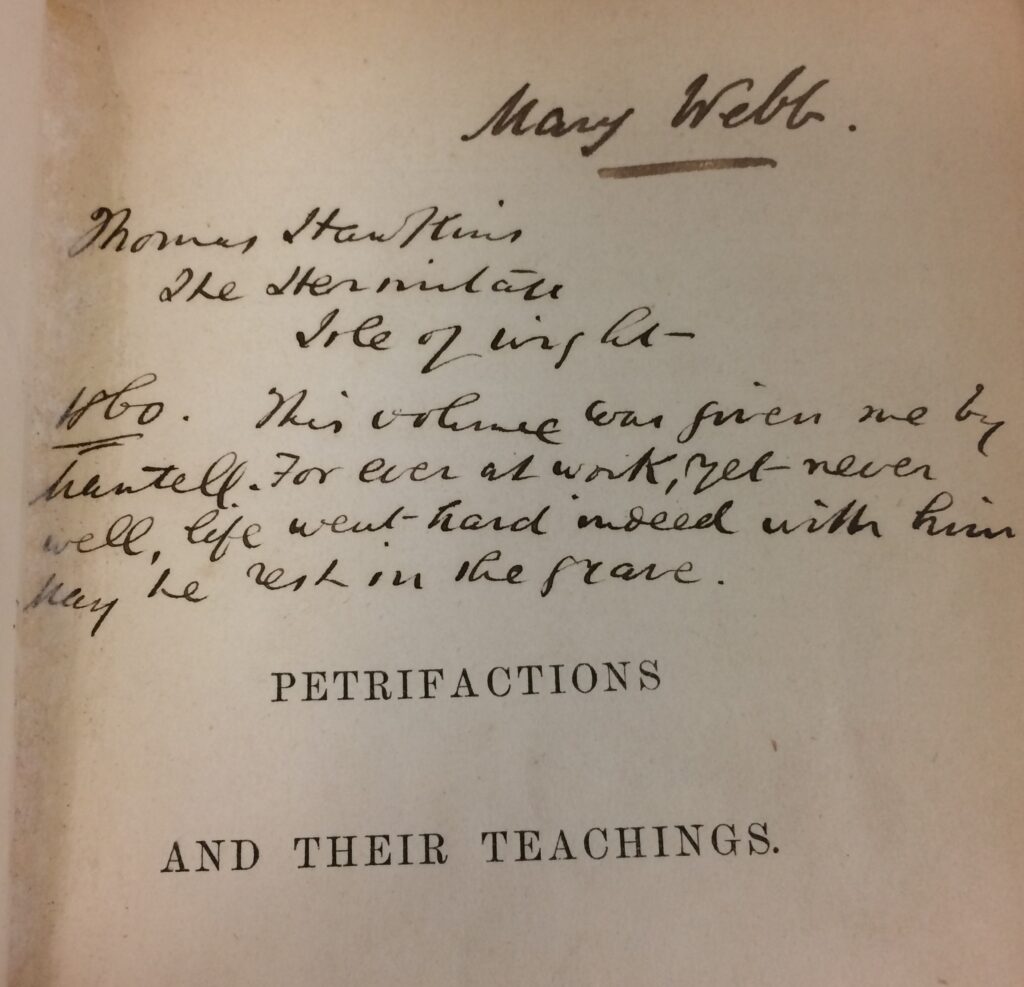

The first mark of ownership we find in our copy of this book is the underlined signature of Mary Webb near the top of the half-title page. Unfortunately without any further contextual information we are probably going to be unable to firmly identify Mary Webb, other than to say that the signature does not seem to match that of the well-known novelist and poet by that name (see some examples at Stanford University’s Mary Webb Digital Archive). But maybe we’ll get lucky … read on!

Just below the Mary Webb signature is the following inscription:

Thomas Hawkins

The Hermitage

Isle of Wight

1860. This volume was given me by

Mantell. For ever at work, yet never

well, life went hard indeed with him.

May he rest in the grave.

The Author, Gideon Mantell

Before turning to Thomas Hawkins, we would be remiss not to consider Mr. Mantell, the author who Hawkins describes as “For ever at work, yet never well.” Gideon Algernon Mantell (1790–1852) was a doctor by training, with a specialization in midwifery, but an avid geologist and what we would now call a paleontologist by avocation. From his youth he took a great interest in the fossils of his native area, around Lewes in Sussex, and he read his first academic paper before the Linnean Society in 1814, “A Description of a Fossil Alcyonium from the Chalk Strata near Lewes.” This was the first of many scientific papers and books written by Mantell: they include The Fossils of the South Downs (1822, featuring many excellent engravings by Mantell’s wife, the former Mary Ann Woodhouse), The Geology of the South-East of England (1833), Thoughts on a Pebble (1836), and The Wonders of Geology (1838). He is credited with the first description of four of the five dinosaur genera known in his lifetime, and his collection of fossil remains was of such great importance and repute that it was opened as a museum at Brighton. When this venture failed, Mantell sold his collections to the British Museum in 1838 for £4,000, and moved to London, where he opened a medical practice on Clapham Common.

Mantell suffered a terrible carriage accident in 1841, which left him with a painful spinal injury. While he continued to lecture, research, and write articles and books, including the volume considered here (one of his final publications), Mantell was in great pain for the final years of his life, and took heavy doses of opium for relief. His death in November 1852 is believed to have been caused by an overdose of the drug.

The Annotator, Thomas Hawkins

Thomas Hawkins (1810–1889), the son of a wealthy farming family from Glastonbury in Somerset, was, like Mantell, an early fossil enthusiast, though his inclinations tended more toward the purchase of fossils dug up by others. He became known as a talented preparer of fossils for presentation and exhibition. He acquired many key specimens, including some from Mary Anning at Lyme Regis, and in 1834 he published his first book, Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri. A second book, The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons, followed in 1840. Both were lavishly illustrated and filled with Hawkins’ distinctive flowery prose. He also later published some volumes of equally florid poetry.

Hawkins met Mantell in 1832, and the older man appreciated Hawkins’ taste in fossils, but worried that perhaps he wasn’t entirely sane: in January 1834, anticipating the publication of Hawkins’ book, Mantell wrote to a friend “The fact is, Mr. H. is a very young man who had more money than wit, and happened to take a fancy to buy fossils.” The specimens themselves were so worthy of note, though, that both Mantell and his colleague (and sometime rival) geologist William Buckland both examined them and recommended that they be purchased for the nation. The trustees of the British Museum agreed in late 1834, and for £1310 the first collection accumulated by Hawkins went to London; they are now housed in the Natural History Museum.

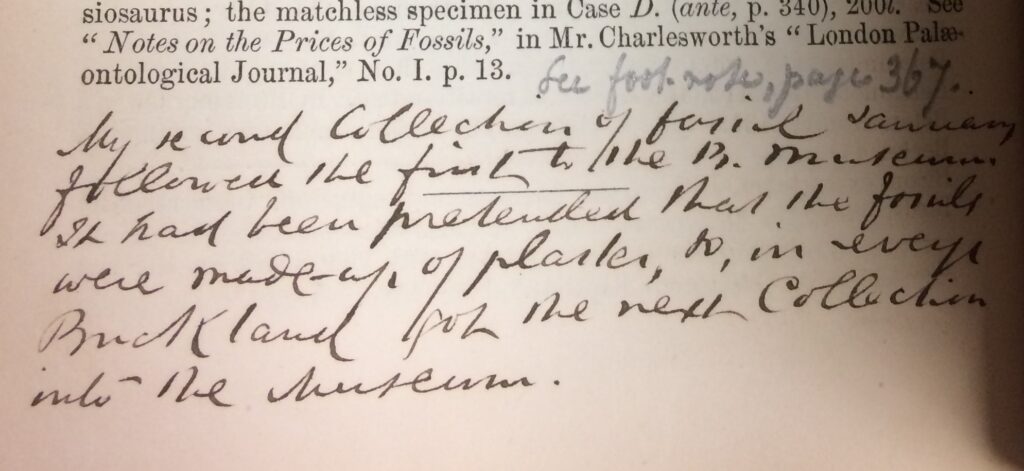

Controversy quickly arose, however. The curator responsible for the specimens once they arrived at the Museum, Charles König, reported to the trustees in February 1835 that he had made a “discovery of a rather vexatious nature,” finding that several parts of the specimens had been restored or filled in with plaster. A committee of the trustees suggested that the supplied parts should be colored so as to clearly delineate them from the original fossil material, which was ultimately the decision taken. Buckland wrote in response that he had known of the restorations beforehand, and had even “often remonstrated against the practice” to Hawkins, but that obtaining perfect specimens would be “all but impossible.” In any event, he continued, “were he again to value the collection, he should fix a larger rather than a less price upon it.”

The kerfuffle went so far as to be discussed by a parliamentary committee, but this first battle notwithstanding, a second collection of fossil saurians was purchased from Hawkins for the Museum in 1840. Bad feelings continued to mount, though, and in 1848 Hawkins self-published a stinging Statement Relative to the British Museum, in which he blasted the museum’s trustees and the curator for the perceived ill treatment of both himself and his collections. He reprinted there a pair of 1841 letters in which he decried the transfer of his specimens out of the oak cases in which he had housed them and the addition of color to the restored places, and protested against the addition of an “ostentatious announcement conspicuously placed on the fossil, ‘That all the coloured parts are restorations in plaster-of-Paris.’—Can anything show a more insatiable spite than this?” He demanded the removal of this notice, “which inasmuch as the public know full that the gaudy portions are restorations, only prompts a reflection upon my character.” Even in 1847 he was still urging that this sign be taken down, writing to Lord John Russell in his capacity as a museum trustee: “As your Lordship understands the position in which one gentleman is put by another who implicates his honour, I have no doubt that your Lordship will feel it a duty to move The Trustees to remove an advertisement which exposes me to be shot in a duel.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, when Hawkins had additional collections ready to pass along to new homes, they did not go to the British Museum, but instead to the natural history museums of Cambridge and Oxford. A note on page 490 of our copy of Petrifactions and their Teachings reflects this:

My second Collection of fossil saurians

followed the first to the B. Museum.

It had been pretended that the fossils

were made-up of plaster, so, in revenge

Buckland got the next Collection

into the Museum.

It wasn’t just Charles König and the Museum trustees who provoked Hawkins to frequent eruptions of wrath, however. He was widely known for his near-constant squabbles with, well, just about everyone. A memoir of Hawkins written by Joseph Clark III of Street in Somerset, written about 1920 but unpublished until 2003, concludes by saying “To sum up the character of such a man is difficult; that he had abilities and skill there is no doubt, but he is evidently one who was living very near the border line between eccentricity and criminal insanity.”

Hawkins eventually moved to the Isle of Wight, where he lived in a house known as the Hermitage. An 1887 entry in the directory Men of the Time reported that Hawkins “has taken a great interest in politics, but his deafness has rendered it necessary that he should confine his political activity to writing.” He published an initial volume of his Life and Works, also in 1887, but had not completed the next volume by the time of his death in 1889.

The Joseph Clark memoir includes the line “somehow he must have got money one theory was by marrying women with large fortunes ….” and Clark recounts how at some point in the 1860s Hawkins “made more disturbance, at Lockhill: a little higher up than Piper’s Inn lived a Miss Short, who, having some property, Hawkins thought would make him a suitable, I think, 3rd or 4th wife, but Miss Short was not taken in by the plausible rascal: so Hawkins raised scandalous stories about her thereby giving great pain and annoyance …”

But Who Was Mary Webb?

In his commentary on Clark’s memoir, Michael A. Taylor notes the discovery by Jehane Melluish that Hawkins had actually been married at least once, and that his wife’s name was … Mary Webb, the very name written on the half-title of our book! Taylor’s 2004 Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry for Hawkins provides more information: Mary Webb was the daughter of James Webb, Esq., and was living in Northumberland Street, London at the time of her marriage to Hawkins on 30 June 1855 at the parish church of St Martin-in-the-Fields in London. Using the Ancestry.com database, you can view a scan of their marriage record from the original in the City of Westminster Archives Centre. By the end of the next year the two had separated, but when Mary died on 8 June 1858, she left Hawkins a not insubstantial sum of money, and it is very likely that this book also passed to Hawkins after the death of his wife. This would make Hawkins’ own inscription on the half-title, indicating that he received the book from the author, as unreliable as much of his other prose.

A bit more exploration at Ancestry.com reveals some additional information about Mary Webb’s family background. Her father, James Webb, Esq. (1760–1822) was a prominent citizen and brewer of Wokingham in Berkshire, and her mother was Jane Elizabeth Ogbourn (1762–1813), originally of Guildford in Surrey. Mary had two sisters: Jane (1795–1847) and Eliza (1797–1851). In their youth the sisters were neighbors and friends of the author Mary Russell Mitford (1787–1855), and several of their letters back and forth can be found in Digital Mitford. In a letter of 3 April 1815 to Sir William Elford, Mitford writes that she is sending a copy of a monody she wrote to mark the death of Jane Ogbourn Webb, saying that the verses “are not worthy of their subject – who was (& it is saying every thing at once) almost as charming a woman as Mama. Her daughters are my most intimate friends – three sweet girls all under twenty.”

English census records, also available via Ancestry.com, even reveal that in 1851, Thomas Hawkins and Mary Webb were both lodgers in a Cheriton, Kent house owned by Charlotte Cooper. Perhaps this was where they met and discovered a shared interest in fossils?

We may not be able to determine much more about how Mary Webb came to acquire her copy of Petrifactions and their Teachings, though we can reasonably conclude that it belonged to her prior to her 1855 marriage to Hawkins, as she signed it with her birth name. Perhaps she herself obtained it directly from the author before his death. We will certainly be grateful to receive any additional information any readers of this post can provide.

* * * *

Mantell, Gideon Algernon. Petrifactions and their Teachings: or, a Hand-book to the Organic Remains of the British Museum. London: H.G. Bohn, 1851 (Special Collections QE716.M29 1851).

For Further Reading:

Bonney, George Thomas. “Gideon Algernon Mantell.” Dictionary of National Biography 1885–1900 36. Available online via Wikisource.

Carroll, Victoria. “‘Beyond the Pale of Ordinary Criticism’: Eccentricity and the Fossil Books of Thomas Hawkins.” Isis 98:2 (June 2007), pp. 225–265.

Dean, Dennis R. Gideon Mantell and the Discovery of Dinosaurs. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Hawkins, Thomas. Statement Relative to the British Museum. London: 1848.

“Hawkins, Thomas” in Men of the Time: A Dictionary of Contemporaries. Twelfth Edition. London: 1887, p. 504–505.

Mitford, Mary Russell to Sir William Elford, 3 April 1815. Digital Mitford. https://digitalmitford.org/getLetterText.php?uri=1815-04-03_Elford.xml.

O’Connor, Ralph. “Thomas Hawkins and Geological Spectacle.” Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 114:3 (2003), pp. 227–241.

Taylor, Michael A. “Joseph Clarks III’s Reminiscences about the Somerset Fossil Reptile Collector Thomas Hawkins (1810–1889).” Somerset Archaeological and Natural History 146 (2003), pp. 1–10.

Taylor, Michael A. “Thomas Hawkins.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, version of 26 May 2005. https://doi-org.proxy.binghamton.edu/10.1093/ref:odnb/12682.

Leave a Reply

View Comments