This is the third in a series of three guest posts by Isaac “Zack” Ben-Ezra ’22 about an independent study project he undertook in Special Collections during the Fall 2021 semester with Professor Bridget Whearty and Special Collections Librarian Jeremy Dibbell. Read the first and second posts.

As I have discussed in my previous two blog posts, in Fall 2021 I was engaged in an independent study researching and cataloging Binghamton University’s six incunabula for the Material Evidence in Incunabula initiative (for more on MEI see my first blog post). During the process which involved carefully leafing through every page of our library’s pre-1501 printed books I found some pretty amazing stuff that had gone long unnoticed and in some cases uncataloged.

I write this blog post not as a self-promoting testament of the work that I have done, but as a means to highlight three things: the amazing resources that Binghamton University has to offer but that too often go unrecognized, the opportunities available to students looking to take initiative in outside-the-box projects, and, quite simply, some super-interesting things about these books.

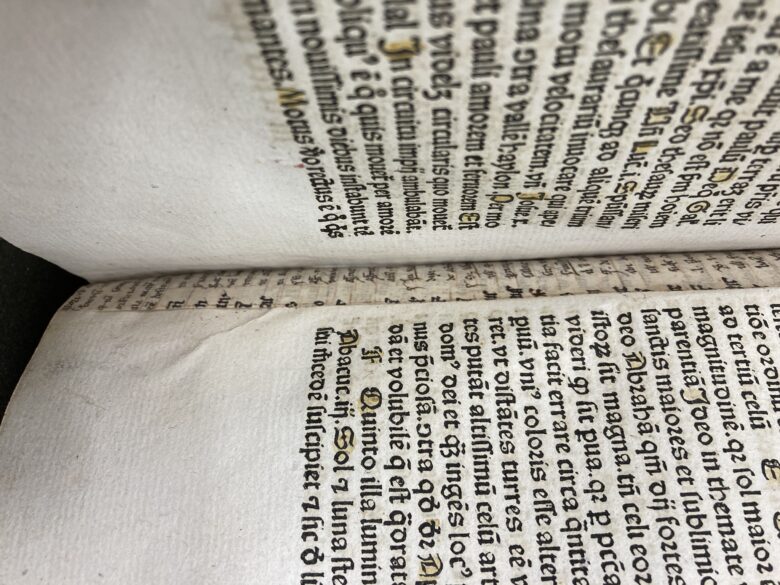

One of the first, and most notable, things I stumbled upon while examining one of our incunabula was manuscript waste in the bindings of two of the six books. These pieces of manuscript documents were bound into early print books to provide supporting structure to the books. It is referred to as “waste” because of the status it held at one point in time. They found their way into these books because they were likely lying around binding shops and were bound into the books just like we use and repurpose scrap paper lying around our houses and workspaces. Now to us, it is more like manuscript treasure!

Manuscript binding waste (like the example shown above) can provide valuable information on pieces of works that are otherwise lost but have been preserved by being bound into the gutter of early print books. They can also be used to track a book through time and space. If we know the time and place that a particular manuscript fragment is from it may provide us with a data point from where that book was bound.

Here at Binghamton, these pieces of medieval manuscript are not only an awesome unexpected find in the gutter of our books for us book historians, but they are also important historical artifacts that students across disciplines can study and explore on our campus. These fragments provide additional opportunities for hands-on interdisciplinary study. The texts of the manuscripts can be studied by Latin students, the pigments by material studies classes, and the objects themselves by medieval studies classes (just to name a few). We are fortunate enough to have these books and their surprise hidden manuscripts. We have an opportunity to learn from them and they have a lot to teach us.

“Incipiunt Aurei sermones” (c. 1485), leaf dd8r.

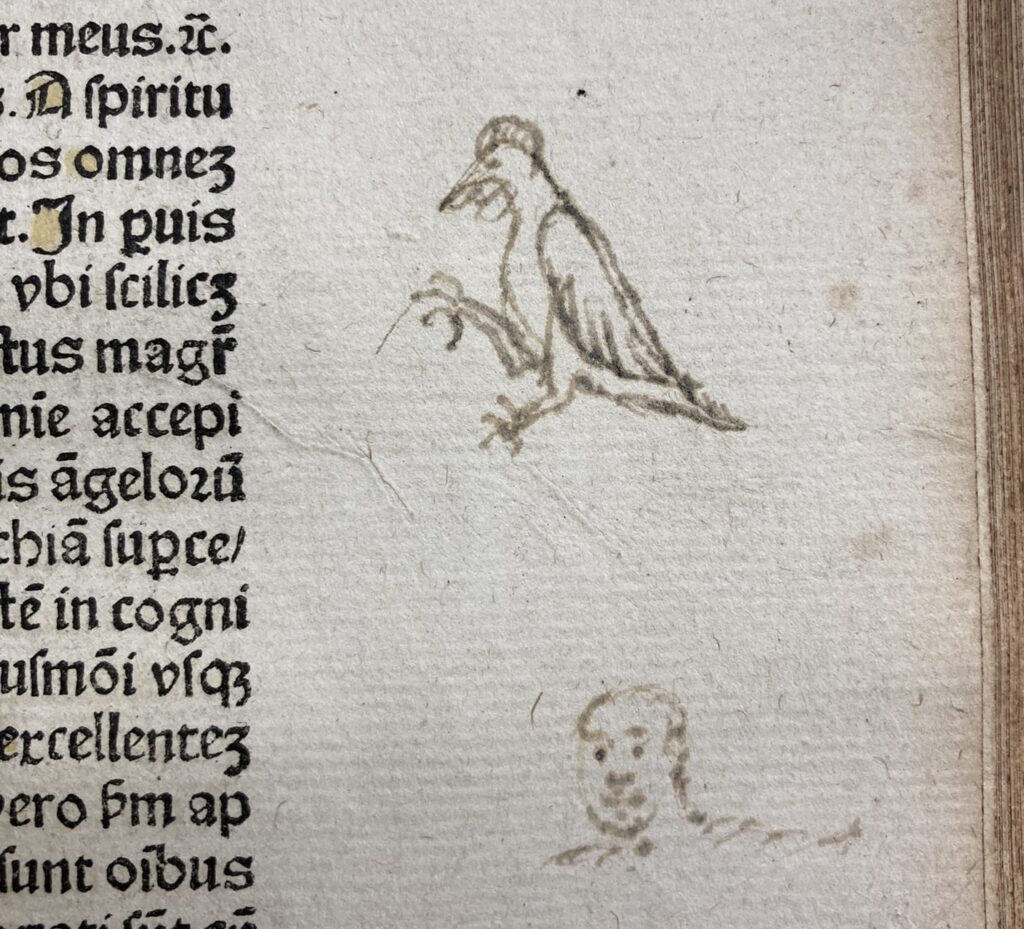

An interesting realization I had while leafing through these books was that the people who once interacted with them, even if more than 500 years ago, were real people who behaved in ways pretty similar to myself. This really became evident to me when I came across a handful of playful doodles. These doodles (shown at left) of a bird and a man’s head humanized my perception of the people who once interacted with this book. The artists behind these doodles were no longer just “those archaic and probably fervently religious people.” They became real people who read books, naturally got bored, and doodled in the margins just as I do.

This personal change in perception was valuable to my research on these books. It reminded me that these objects were used by actual people and have to be treated as such. The wear and tear on these books was a result of these people and the way they interacted with these books. Understanding this relationship between person and book is vital to using these physical signs of wear and tear to better understand the history these books have encountered.

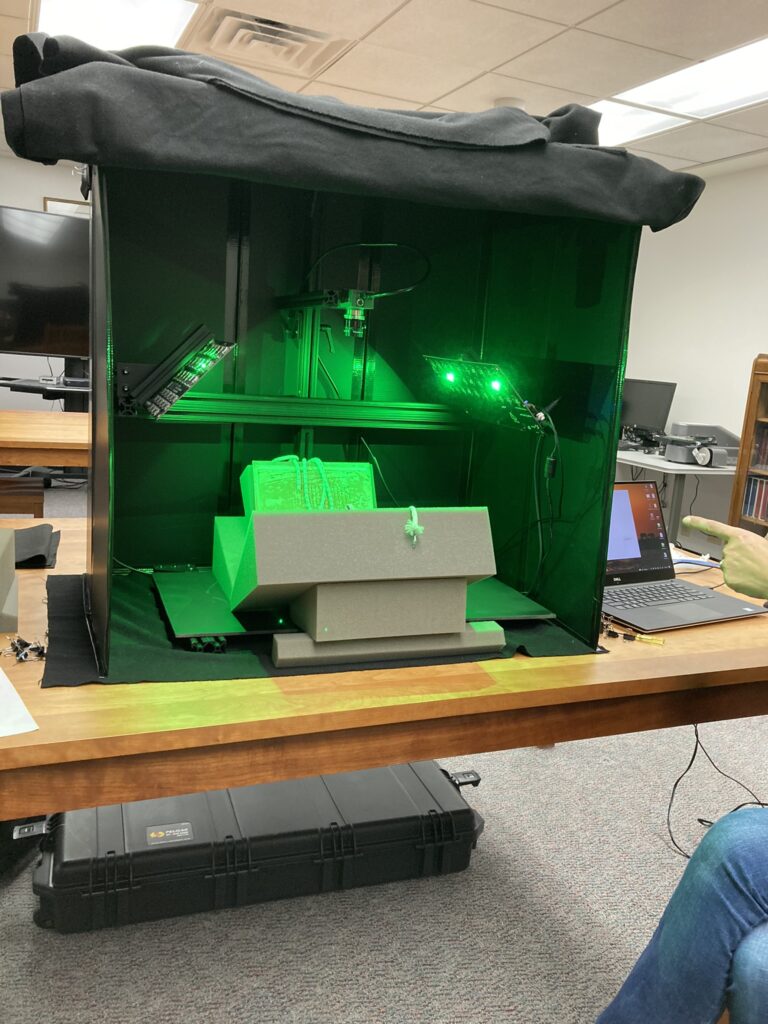

Some of the most interesting research that we are doing on these books is taking a deeper look at the things we cannot see with the naked eye. During the first week of December, researchers Roger Easton and Tania Kleynhans from the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) came down to Binghamton and used a new, low-cost multispectral imaging system and software they are developing (with funding from the NEH) to take pictures of some of our books.

These pictures were not typical pictures. The system developed by RIT took pictures of the books in various spectra of light—more broad than our human eyes can see—and used those images along with their software to capture color that is on the page but that cannot be picked up by our human eyes.

While these multispectral images are very cool from a scientific standpoint (although admittedly I can’t tell you much about the science behind it), the technology can also teach us valuable pieces of information about our books. There are many instances throughout our incunabula where notes or text appear either faded or crossed out. Using this technology, we may be able to uncover some of them.

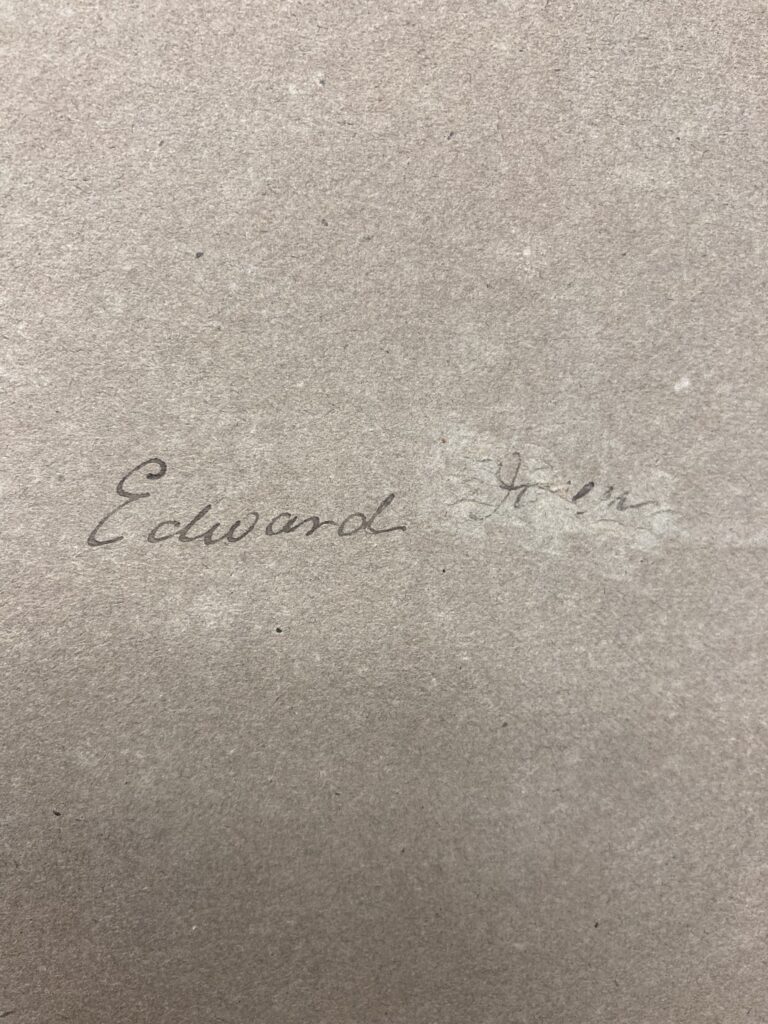

Take for example the image at right. It is from the front pastedown of one of our incunabula, Johannes Nider’s Incipiunt Aurei sermones totes anni de tempore, printed at Cologne around 1485. It seems to be an ownership inscription of someone who was likely in possession of the book at some point in time. The first name can pretty easily be made out as “Edward,” but the last name seems to be crossed out and illegible. Using multispectral imaging we hope to be able to learn what was once written there, thereby identifying an owner of the book at one point in time. While that piece of information may seem of little value, it’s quite the opposite! The owner’s name paired with the database of MEI is a super powerful tool that can help us learn more about this particular book’s history. For example, using this mystery-Edward’s full name, we can search for other books in the database that have the same name written inside, and learn about both the book itself, such as its origins and path through time and space, but also about Edward and what his book interests can tell us about him as a person!

As students and members of the Binghamton University community we are privileged by how much the University has to offer. Sometimes opportunities lay dormant for years, or in the case of medieval manuscript waste: hundreds of years, waiting for someone to take advantage of them. I hope that the research I conducted in my independent study has not only shone a light on some of the amazing resources our library has to offer, but also inspires other students to take advantage of a cool opportunity to pursue an interest and through it share their passion with the campus community.

Lastly, throughout these blog posts I have made a point to emphasize the resources that Binghamton University has to offer. While the fancy old books to study and beautiful facilities to learn inside of are nice bonuses, what truly makes Binghamton special are the faculty who care. I want to take a moment to thank my academic advisors for this independent study —Professor Bridget Whearty and Jeremy Dibbell. Throughout the semester Professor Whearty and Jeremy were always there to support me and foster my academic interests and without them this independent study would not have been possible. I am deeply grateful and appreciative for both of them.

Zack’s findings will be incorporated into the MEI records for our incunabula in the coming months.

Leave a Reply

View Comments