This is the first in a series of three guest posts by Isaac “Zack” Ben-Ezra ’22 about an independent study project he undertook in Special Collections during the Fall 2021 semester with Professor Bridget Whearty and Special Collections Librarian Jeremy Dibbell.

Deep in the heart of Binghamton University’s library, behind the double glass doors in the climate-controlled conditions of Special Collections, are six books whose dates of publication situate them uniquely at a major turning point in Western history. These books were printed in the period between 1450 (roughly) and 1501, representing the introduction of movable type printing in Europe and the turn of the sixteenth century respectively. While this period of time is arbitrary, its designation has caused these books to take on immense significance in the study of book history because of their liminality between the transition from the use of manuscripts to printed books as the primary method to record and disseminate information. These books have come to be called incunabula, from the Latin for “in the cradle,” because of their origins in the infancy of movable type print in western Europe.

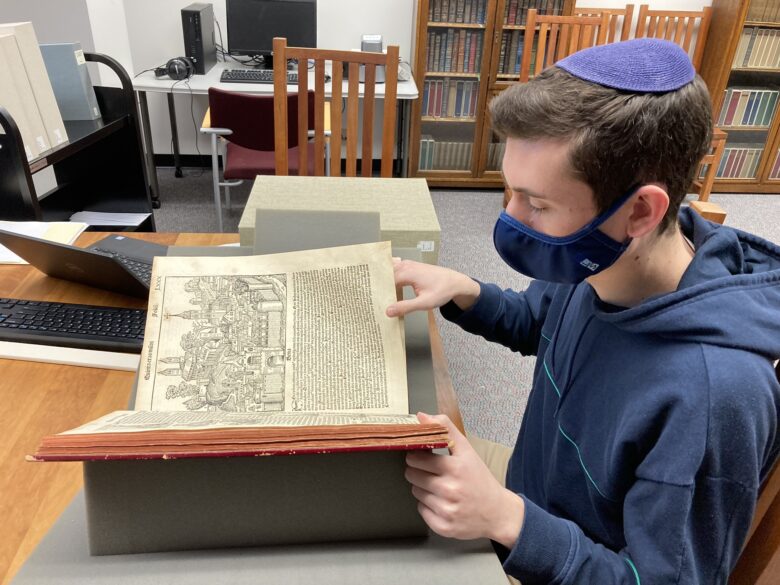

I often get asked how I came to study books half a millenium old books. The question is valid. Out of necessity for care and preservation these books are kept in Special Collections, which makes them difficult to stumble across accidentally. But like so much in life, my encounter with these pieces of history was somewhat happenstance. A few days into fall 2020 I decided to switch into a class on the history of books with Professor Bridget Whearty because it sounded interesting, not to mention the general education requirements benefited me significantly. I enjoyed the class, found the content interesting, and liked working with Professor Whearty. The next semester, I took another class with Professor Whearty on medieval manuscripts and again learned a lot. But throughout both semesters one fundamental thing was missing: hands-on work with these books that we were studying. Due to COVID-19, we were unable to go into Special Collections and study these books hands-on as we would in a normal semester. We made the most of it by studying books virtually, but physical books and their virtual copies are just not the same things. I wanted to touch the books, feel them, smell them, flip their pages, experience them just as the people who had interacted with the book before me had, too.

These books are far more than just a method of transmitting information in written form: they are physical objects who have interacted with countless individuals over their more than 500-year history. These centuries of interactions have left physical signs of use, scars in a way, on the books. These physical characteristics and marks of wear and tear can range from the way the books had been printed and bound, to marginal notes, or rips in the pages. They provide us with clues into how people interacted with these objects over time, thereby also helping us better understand the general people and time period from which each book originated. These physical characteristics of each incunabulum are of paramount importance to my personal research and have the capability to both contribute to the broader world of book history studies, and deepen academic research here in Binghamton. The problem has been, however, that these books have not received the attention they deserve, leaving their keys to history ungleaned and teaching potential untapped.

This is where the Material Evidence in Incunabula initiative, also known as MEI, comes into play.

MEI is an international initiative to record every incunable, making note of small details and signs of use, and then cataloging that information into the publicly available and free database. While the thought of leafing through every incunable in the world may seem both tedious (which admittedly, it is) and unworthwhile, it has immense potential benefits for the world of book history and the institutions that own these books. While turning each page of our incunabula was hard work, the comprehensive data collected on each book has far reaching benefits.

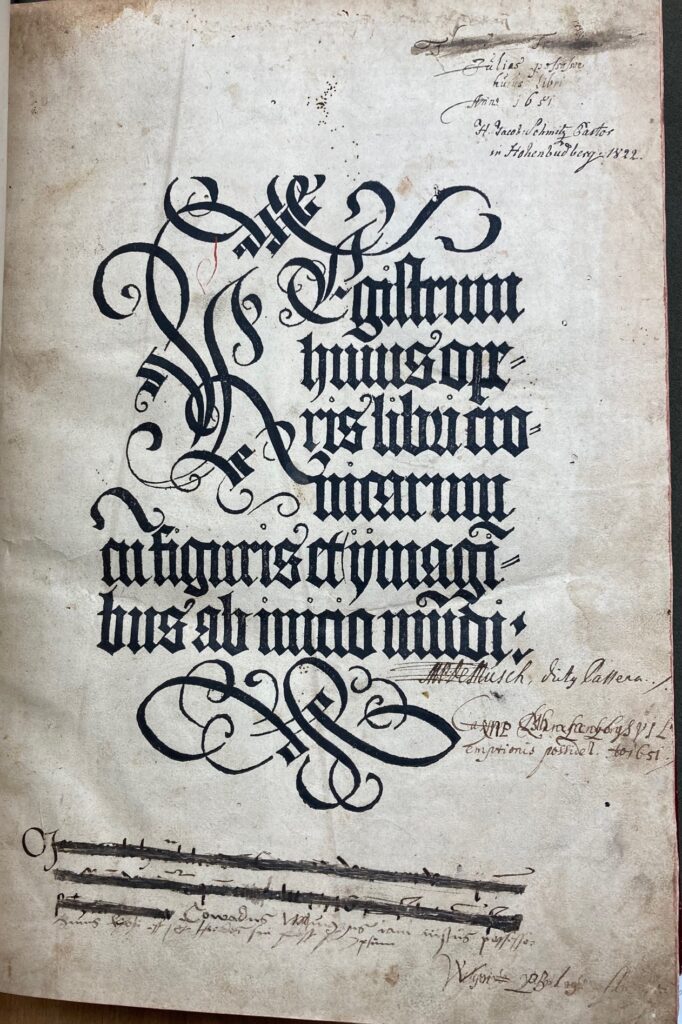

showing numerous ownership marks.

Special Collections Stacks D17.S3

Although an incunable may seem like a single independent entity at face value, no incunable is an island. These books are deeply interconnected with each other, along with the landscape and people they have encountered throughout their history. For example, using MEI, an identifying feature in one book, such as an ownership inscription, can be compared to other books in the database. This could allow researchers to make broader and more substantive claims, such as reconstructing a person’s library and thereby learning more about them. Further, the mysteries of one book could be solved by an otherwise overlooked characteristic of another book. Perhaps a library has a question about where one of their incunabula was printed, while the same incunabule halfway around the world bears an inscription from the printing house. These are the types of mystery-solving connections MEI can create.

But beyond the scope of MEI, the very act of cataloging these books greatly enhances their ability to be utilized here in Binghamton. These books and their features can be used by different classes across a wide range of disciplines to both learn from and continue to contribute to their research. Latin classes can work on translating parts of the books and their notes, sociology classes can examine how minorities are represented in our copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle, classes on European history can see firsthand how the process of early European printing worked, and much more! The first step in being able to utilize the resources that we own is simply knowing what we have.

Some other universities and institutions have tens, even hundreds, of incunables. Here at Binghamton, we are truly grateful for our six and I like to think that we love them just a little bit more because of that. These books deserve more attention, and the students of Binghamton deserve to experience the treasures the University has to offer. MEI offers a unique opportunity to put Binghamton University on the map of institutions that hold these important pieces of history, while simultaneously encouraging the continued research of these books through interdisciplinary study and hands-on experience with our incunables.

Future posts in this series will discuss the complexities involved in producing these books, and explore some of what we found when we gave them a very close look.

Fascinating information presented with impressive writing skills. I would love to see more posts like this by students about independent studies and “off the beaten path” projects similarly enhanced by good writing. You have much to be proud of, Zack!