This is the second in a series of three guest posts by Isaac “Zack” Ben-Ezra ’22 about an independent study project he undertook in Special Collections during the Fall 2021 semester with Professor Bridget Whearty and Special Collections Librarian Jeremy Dibbell. Read the first post.

As my time in Binghamton comes to a close and the days and weeks to graduation wane, I am thinking about what I am thankful for. Sure, there are the obvious, though no less important, things to be grateful for: my family, my education, and all the opportunities life has afforded me thus far—but there are also the little things that all too often go unrecognized. My independent study in the library this past Fall has shone light on one particular object that I believe is all too often taken for granted: the (not so) simple book.

To fully appreciate the beauty of the modern book in the West it is important to reflect on its beginning—the world of early-European print in the mid-fifteenth century. These early books called incunabula, printed between 1450 and 1500, look fairly similar to any other book today: they were made up of sheets of printed paper, folded and often bound between two covers. But upon a more in-depth look at the process of creating one of these objects, it quickly becomes apparent just how amazingly intricate and labor-intensive creating these books was.

Let us start with the medium upon which these books are printed: paper. It’s pretty easy to take paper for granted today. I can go to Walmart and buy a ream of paper for around the same price as a typical coffee-drink at Starbucks. But in the era of early print, paper was far and away the most expensive resource in the book making process. Each sheet was made by hand, starting with straining the pulp on a mold and subsequently pressing and drying it. This process would continue on repeat within the papermill with hands-on manpower involved each step of the way.

From there, the paper would be transferred to a printing shop. While the advent of movable type printing in Europe allowed printing to be streamlined and more uniform, by no means was the process as easy as clicking CTRL+P. To start, each individual letter had to be hand-carved as a mirror image and then cast into a small piece of metal which would then be assembled, also by hand, into the correct order in the chase, the frame which held the pieces of moveable type. Once set and locked in place, the type would be inked and pressed against the paper. Once dried, someone would need to fold the sheets and bind the book, another complicated and labor intensive process.

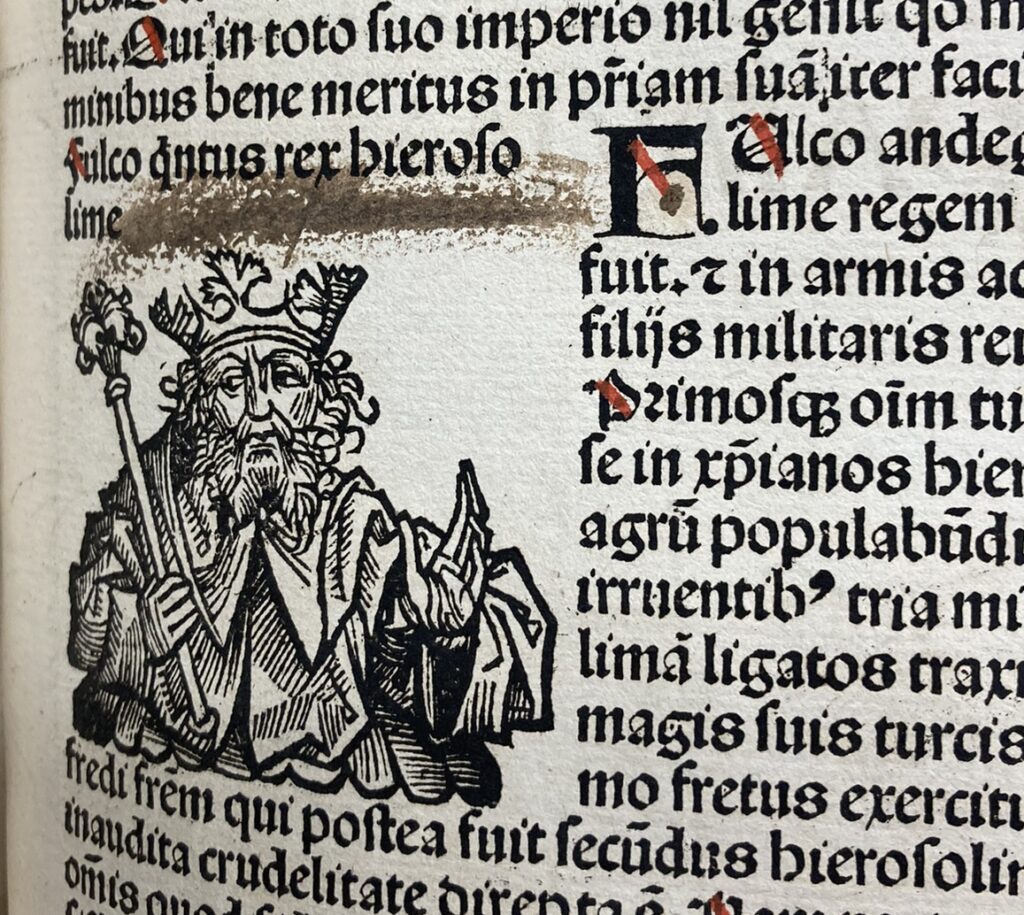

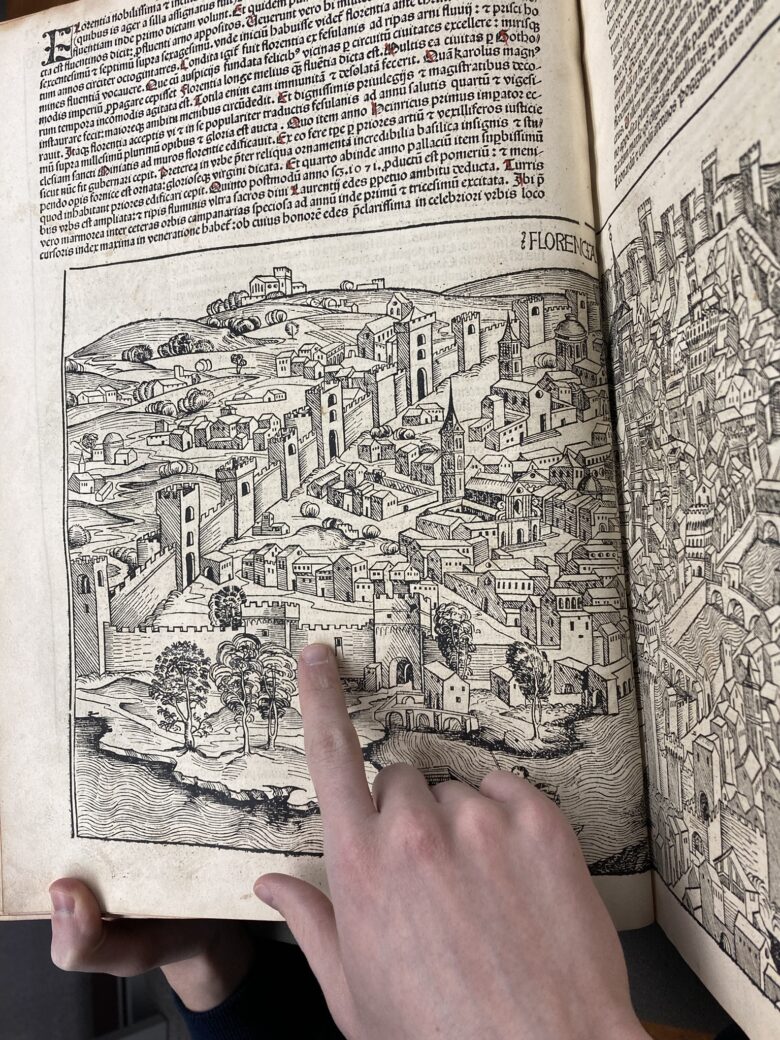

Adding illustrations to an early printed book added a whole new level of complexity to the process. Many incunabula contain images of some sort, often in the form of woodblock prints such as in our library’s beautifully intricate copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle. This meant that someone needed to hand carve an image from a piece of wood, but if that does not seem difficult and complex enough, the image had to be carved inverted so as to appear correctly when pressed against the paper. Just imagine trying to carve an image out of a block of wood. Now, imagine needing to carve that image inversely. That was the mental and skilled wherewithal required of an early-print woodblock artist.

The advent of movable type printing in Europe revolutionized the ability to easily disseminate information throughout the continent, which in turn had major effects on the world. However, this print revolution was by no means an automated method as we think of printing today. There was painstaking human labor involved in every step of the process. Still today, more than 500 years later, we both benefit from and feel the effects that this laborious process had on the world. It may seem far removed, but the print we encounter on a daily basis and the wide availability of information available to us today was built and developed on this process of printing.

Studying these early printed books has given me an appreciation for the modern world that we live in, while simultaneously helping me recognize and be thankful for the painstaking human labor and ingenuity over the course of human history that has guided us to where we are today. As the semester comes to a close, I hope that we can all take a moment out of our day to appreciate the little things that too often go unnoticed but have profound impact on our lives. I also encourage everyone, if interested, to make an appointment in Special Collections in the Library and see firsthand some of the early books that Binghamton owns. These books are truly amazing pieces of history and should be fully utilized by the University community.

The final post in this series will explore some of what we found when we looked closely at our incunabula.

Leave a Reply

View Comments