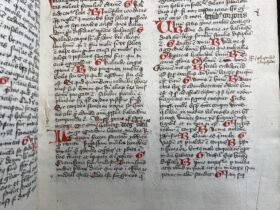

Sometime around the year 1491, the German cartographer Henricus Martellus produced an influential map of the world, which was likely used by Christopher Columbus on his 1492 expedition to the Americas.

Naturally, Martellus made sure to note all the wildest rumors about the locations he had charted out. Text over south Asia claimed that the Panotii people of the region had ears so big they could curl up and sleep in them, Dumbo-style. A cartouche over the Indian Ocean warned of “a sea monster that is like the sun when it shines, whose form can hardly be described, except that its skin is soft and its body huge,” which experts think is a description of orca whales. Japan was labelled with the tantalizing note “precious stones are found on these islands.”

But time was not kind to these fantastic messages, and the vast majority of them were muted over the centuries by material degeneration. The words either faded out with time, or had been obscured by damage. We would never know about them at all if it weren’t for the emergence of new techniques in imaging science over the last two decades, which can decipher damaged, vandalized, or otherwise unreadable texts with startling precision and accuracy.

“There’s text all over the map,” Roger Easton Jr., one of the key players in this fledgling field, told me over the phone. “But it had all faded; you couldn’t really read much of anything.”

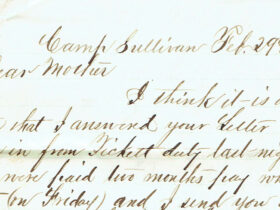

Easton is one of the only people in the world who knows how to resurrect these lost writings from obscurity, which means he frequently ventures to fascinating destinations in order to study rare manuscripts. As a professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology and one of the leaders of the Lazarus Project—an organization of specialists involved in deciphering historical documents with multispectral imaging—he has collaborated with scholars, scientists, and other specialists all over the world.

“That’s the best part,” Easton told me. “Meeting the people is the best part. They are so appreciative when you pull something out.”

These interdisciplinary teams are able to unlock these difficult texts by capturing them over a wide range of wavelengths. In much the same way that an X-ray image of the sky yields a different perspective on the universe than an infrared image, pseudocolor pictures of text can extract words that have been invisible to the naked eye for centuries. It’s like The Da Vinci Code, only with fancy cameras and better dialogue.

“[The Martellus Map] was among the more fun ones we have ever done,” Easton told me. “In some methods, you can see the scribe lines but you can’t see any text at all. In other methods, the text pops right out. I know we didn’t get all of it, but I think we got quite a lot of it.”

“This is sort of the ultimate treasure hunt.”