Sometime in the fourteen-sixties, a private Christian devotional was produced in northern France. Its pages were expertly calligraphed, embellished with gold leaf, and decorated with sprays of blue acanthus, pheasants, swans, peacocks, and dancing villagers. There were seventeen full-page Biblical illustrations. Its final leaves contained an early owner’s translations of a few Latin prayers into medieval French. Such opulent books of hours became prized collectors’ items among the cognoscenti in later centuries, which may be how this one found its way into the private library of a nineteenth-century British collector named Edward Arnold. By this time, it had received a new morocco binding and its illustrations had been touched up, probably by the artist Caleb William Wing. In the nineteen-twenties, Arnold’s estate sold the book to Sotheby’s; it appeared on the auction block again at a Christie’s sale, in 2010, where it sold for twenty-five thousand pounds (then about forty thousand dollars) to an anonymous bidder.

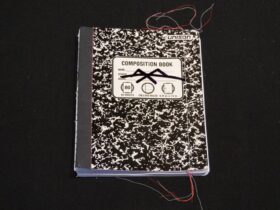

By the time that Elaine Treharne, a medievalist at Stanford, purchased the manuscript from a colleague for seven hundred dollars, in November, it resembled not so much a book as an old, empty wallet. Within its nineteenth-century leather binding and silk flyleaves, only the seven rearmost of the book’s original two hundred and fifty-four leaves remained. Treharne told me that, at first, she wasn’t alarmed by the state of the book, which she had purchased as a teaching aid. The extraction of illustrations, calendars, and other decorative pages from books of hours was common in the early nineteen-hundreds, which is when she assumed the dismantling had taken place.

But she was intrigued by the book’s intact ex libris, which identified Arnold as a former owner. The bookplate led her to an online version of Arnold’s privately printed catalogue; by entering his brief description into Google, she was able to track down the book’s sale lot from its 2010 Christie’s auction. Here she discovered photographs of several of the absent illuminations, a partial ownership history, and a surprising fact: Christie’s had listed the book as “APPARENTLY COMPLETE.” In other words, the devotional had been taken apart—“broken” is the industry term—not a hundred years ago, but within the last three years. Its leaves had been stripped for individual sale by a modern-day dealer.

“I was almost physically sick,” Treharne told me. “I could not believe what I had in front of me.”

Read more in The New Yorker here