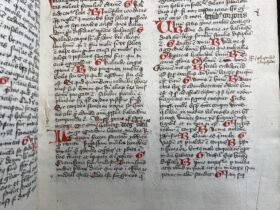

Centuries-old books on parchment may soon become more accessible than vital scientific writings and data from early computers.

The Washington Post Magazine has a riveting account of the application of new imaging techniques to palimpsests — manuscripts recycled by scribes on valuable parchment with remaining traces of previous texts — in the library of the ancient Monastery of St. Catherine in Egypt’s Sinai desert, a remote site largely spared by the conflicts that destroyed records and art work elsewhere in the Middle East. Its preservation system for historic records can be described only as benign (divinely guided?) neglect:

“That’s something that is so important about the library,” says Father Justin, a Texan first attracted to Greek Orthodoxy by a love of Byzantine history who joined the monastery in 1996. “Because it was built up by the living community here, it’s still in its original context, and that’s an added dimension to every manuscript.”

The monastery holds at least 130 palimpsests, all from medieval times. One of the richest sources of palimpsests has been a collection known as the New Finds — “new” being a relative term in a place so old.

Across the monastery from the imaging room, there is a small wooden door that could once be reached only by ladder — and few apparently made the climb. Behind that doorway and through two more is a storage space probably untouched from the 18th century until 1975. It was then, while cleaning up damage from a nearby fire, that the monks ended centuries of procrastination and inventoried the nearly forgotten storage area.

(One of the paradoxes of archaeology that it’s often destructive events like earthquakes and road building that make people realize what’s been under their noses all along.)

Techniques developed to reveal the original manuscript of Archimedes in the palimpsest now deposited at the Walters Museum in Baltimore may change our understanding of the classics of literature, philosophy, and religion. Imaging will also help assure its survival in an online database available to scholars around the world:

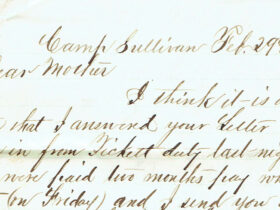

Once digital images of documents are sufficiently distributed around the world, the information they contain becomes exponentially safer.

As Doug Emery, an independent database handler in Baltimore whom the team calls its Lord of Minutiae, puts it: “We believe the way to protect books is you hold them close, and the way you protect digital data is you give it away.”

An even bigger paradox may be, though, that centuries-old books on parchment may soon become more accessible than vital scientific writings and data from early computers, perhaps to be called the Paleocybernian Era.

Read more here