By Mark Schrope, Published: September 6

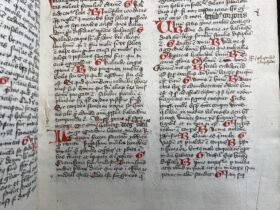

MOUNT HOREB, Egypt — Michael Toth points at a computer screen filled with what seems to be a jumble of Arabic and Greek letters.

To get to this jumble, he has traveled from Washington to an isolated, fortress-like monastery in the middle of the Sinai Desert, home to the oldest continuously operating library on the planet.

He has helped assemble a global team of scientists that arrived with cutting-edge technology at this spot, three hours by taxi from the nearest commercial airport.

The image he has paused to appreciate is one of a steady stream coming from the room next door, where a high-definition camera is focused on one of the monastery’s rare and priceless ancient manuscripts. The manuscript rests in a cradle that looks like a chair tilted back at an angle, but with hydraulic lines and strange lights attached.

One more room over, in the makeshift command center, specialists are scrutinizing the day’s results, and the monastery’s head librarian, a wispy gray beard to his stomach, waits in a red velvet chair for the next request to turn a fragile manuscript page.

“This is the first time since the 9th century that anyone has seen this,” Toth says of hints of text below the more visible words.

The first time since the era of Viking invasions and Charlemagne.

The more prominent legible words are 1,200 years old and are interesting enough, but they are not what the scientists are here for. The team is really after the overwritten text from centuries earlier, last seen by the person who scraped it away to recycle the precious animal-skin parchment.

Such erased texts are known as palimpsests, and until their pages enter the imaging room, no one alive now or, in many cases for more than a millennium, can say for sure what has been hidden. The work is tedious, like carefully brushing away sand at a traditional archaeology dig, but the promise of what can be found is a powerful motivator.

Read more here